Postby Lord Roem » Sun Aug 17, 2014 10:58 am

“I think he has a very unusual intellectual ability, but at the same time he seems to have a very unbalanced mind, which is a real danger at a time like this”

- Andrew Bonar Law on Winston Churchill

[center]_______________________________

Three[/center]

(Taken from “Deadlock: The Great War in 1915” by Basil Liddell-Hart, Hammond 1954)

In January 1915, Lieutenant Colonel Ernest Swinton formally approached the War Office with his ambitious proposals for a ‘machine gun destroyer’ - an armour-plated mechanical vehicle with a crew of ten, mounted on tracks, and armed with repeating rifles. Shielded from enemy fire, the machine would be able to methodically advance at a speed of approximately four miles an hour, destroying the German positions and allowing the regular infantry to capture the trenches during the initial shock-wave. The concept was immediately supported by both Churchill and the Secretary of the War Council, Maurice Hankey. After internal discussions, the three men were able to persuade the War Office to trial the idea. When the prototype fell into a trench and was unable to escape during trials, the War Office abandoned the idea, but Churchill was by then already personally pursuing an alternative plan that had been submitted by Major Hetherington of the Royal Naval Air Service.

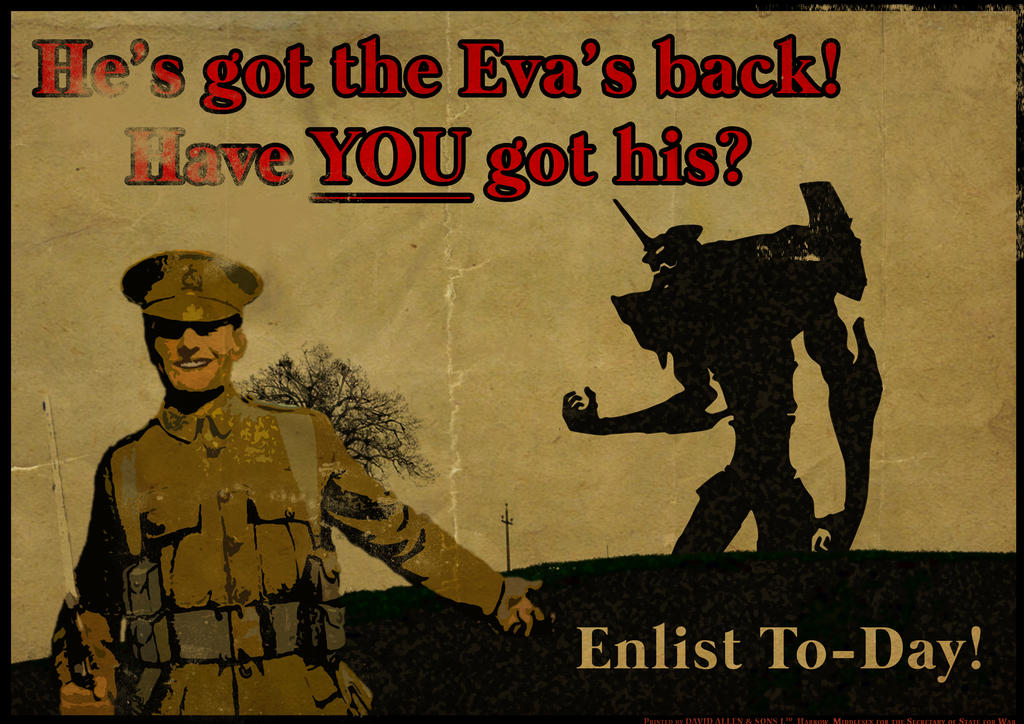

In his capacity as First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill appointed a ‘Landships Committee’ the following month, under the Director of Naval Construction, Tennyson d’Eyncourt (relative of the former Poet Laureate) to further develop the idea. In March, Churchill took the controversial step of approaching a £70,000 budget for the project - despite clearly having nothing to do with the Admiralty’s jurisdiction. Whilst the Committee’s early plans for something that amounted to little more than an armoured personnel character bore little resemblance to Gendo Ikari’s ‘Unit 01’ that would play such a crucial role in the Somme the following year, Churchill nevertheless deserves to take considerable credit for promoting the concept of the ‘Barrel’ and - obviously - the ‘Evangeliser’ at Cabinet Level.

The rest of the Cabinet eventually stumbled upon the Committee’s existence in the summer, with the Committee becoming a joint Admiralty-War Office affair that June. Under the guidance of the new First Lord - Arthur Balfour - trials into the prototype “Mks. I, II & III” took place over the following few months, although many of the forthcoming designs would later be superseded by the Ikari-led designs, which were to come to light during the Christmas period.”

-----

(Taken from “Churchill - A Life” by Emily Fitzsimmons, Blue House 1965)

The Gallipoli campaign dragged on throughout the summer and autumn. Despite the mounting number of casualties and almost total lack of progress in terms of advancing against the Ottoman lines, Churchill continued to mount constant support for the operation, despite the growing objections of his associates. By the end of October, he was almost entirely isolated within the Dardanelles Committee, the majority of whom had come to the conclusion that the entire operation was unsalvageable.

This was not the first time Churchill’s stubborn self-belief had boarded on the delusional. The previous year, the First Lord had visited Antwerp and taken personal charge of the defence of the city, overruling Royal Navy commanders in the field by requesting three battalions of the Royal Marines be sent to take up positions to defend against the German attack. Both the British and the French War Offices were unable to do so, and the city consequently fell on the 9th October. Despite mounting criticism in the press, Churchill telegrammed Asquith, offering to resign in position in the Cabinet in exchange for a high-level command in the field. When the Prime Minister read out the message to the Cabinet, there was a tremendous cry of laughter, and Churchill was recalled home, narrowly avoiding being sacked.

In early November, the Cabinet met to discuss the future of the campaign, with a majority deciding that all troops within Gallipoli should be withdrawn by the end of January. Already demoted to Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster as part of the Conservative conditions on entering the coalition government, Churchill was left with little choice but to resign from Cabinet entirely on 15th November. It was clearly unfair that the First Lord should have been left as the scapegoat for the botched campaign, especially given that Kitchener had been the first senior official to call for an amphibious invasion of the peninsular, and that formal authorisation had fallen upon Asquith personally. Despite being a serving Member of Parliament, he requested (and was granted) a commanding position on the Western Front in January 1916, although he would immediately transfer to a position in Gendo Ikari’s ‘NERVE’ Corps, following his appointment as a temporary Lieutenant Colonel.”

-----

(War Office, London

24th December, 1915)

Eustace Tennyson d’Eyncourt surveyed the room. Despite the door being set fast, the winds nevertheless had found their way through cracks in the frame, as well as gaps in the window planes. The lamp in the corner swayed ominously as another gust swept through the Committee room. At the other end of the table, the civil servant who had been serving as Secretary to the committee sneezed.

“Bless you,” the Chairman of the ‘Landships Committee’ said as the mandarin apologetically snorted into a handkerchief, “and I do apologise for keeping you all so late, gentlemen.”

There was a non-committal murmur from the rest of the room. Rooks Crompton, the committee’s consulting engineer, gave a stare was even icier than the wind.

“This does bring us back to the papers and schematics that have been submitted under Annex Five of the files that you have in front of you,” d’Eyncourt continued, “which I understand have already aroused considerable debate amongst many of you.”

That was putting it mildly. The autumn tests of the Mk. I had been inconclusive, to the extent of threatening the entire existence of the project, with the War Office, and later the Ministry of Munitions, both suggesting that the whole scheme be scrapped and the funding re-diverted into the trench budget. d’Eyncourt, Swinton and the rest of the Committee had been able to mount a spirited defence - aided when the Mk. II had impressed the top brass during later demonstrations. The support of both Sir John French and Douglas Haig - a rare consensus between the two - had also helped matters, and d’Eyncourt had continued to develop the principles over the next few months.

That was, until the mad Japanese professor had appeared. A naked man of Oriental extraction falling from the sky was a curious enough thing in itself, but when the same person had produced - apparently from no-where - schematics for armoured vehicles that were far advanced from those of the entire War Office, heads had turned. Crompton, who had spent the best part of a week pouring over the designs, had been furious at having a year’s work rendered obsolete - but had been talked out of resignation by the Minister of Munitions, who had insisted that the veteran engineer be allowed to take the majority of credit for them. As it was, the Minister - as well as a number of his colleagues - had decided to attend the meeting in person.

“They have indeed caused some - ahem - ‘muted’ discussions at Cabinet,” David Lloyd George said with a wily grin, “if I remember correctly, Lord Kitchener actually asked me if the proposals had been the work of witchcraft.”

“I hope that you didn’t tell him that they may possibly have done so, Minister?” d’Eyncourt replied, “I note that we have yet to receive any confirmation of Mr Ikari’s origins from any of the clerks at the Japanese Embassy.”

“Witchcraft or not,” Colonel Swinton said, “there’s no doubt that the man is a genius, the only question is whether or not we actually manufacture half of the component parts we need to physically construct the thing.”

“And that’s the whole - damn - point,” Crompton yelled, “we have halted construction on a number of machines that are practically complete in exchange for little more than the wild imaginings of a Japanese da Vinci!”

“da Vinci was still a genius,” Lloyd George pointed out.

“But he achieved little of lasting note in the mechanical sciences,” Crompton responded, irately.

“If we can construct them though,” Harold Tennant, the Under-Secretary for War, noted, “surely it is immaterial?”

Lloyd George and Swinton nodded. Crompton glowered.

“What I mean,” Tennant continued, “is that so long as we keep Mr Ikari out of the attention of the media for as long as possible - there is no reason to suggest that these, ‘tanks’ or whatever we call them - emerged from anything less than domestic British ingenuity.”

“DORA will certainly help us in that respect,” the Earl Curzon replied, “that media have always acquiesced to all of our demands in terms of reporting on matters pertaining to military innovation - I see no reason why this should be any different, especially with regard to the presence of a foreign national within the corps.”

“Probably helps us, frankly,” Swinton added, “gives us someone to blame if the whole thing becomes unworkable.”

“I note that we only had these proposals sent to us six days ago,” d’Eyncourt said, scanning the agenda, “how long will it be before we actually have any evidence as to the viability of producing a working prototype?”

Albert Stern, the Committee’s Secretary, quickly looked through his papers.

“Assuming that Colonel Crompton’s works are able to cope with the manufacturing principles,” he said, ignoring another glare, “I estimate that we could have something approaching a working model within the next three months.”

“Excellent,” Lloyd George said, giving an approving nod, “I have every confidence that we can arrange for the Prime Minister to attend the demonstration at Hatfield Park, even if we have to move it to March rather than February.”

“I still advise caution,” Crompton said, arms folded, “I am still uncomfortable at treating a man we know nothing about into the highest echelons of His Majesty’s government.”

“That does remind me,” Swinton replied, “where is our mysterious benefactor?”

“I have taken the liberty of suggesting that he be relocated, under guard at Foster’s - William Tritton’s Lincolnshire works,” Stern replied, “he is being transferred there from Saint-Omer on St Stephen’s Day.”

“What is his current state of mind?” Lloyd George asked.

“He remains calm, but curiously evasive apparently,” Stern said, “which does - obviously - make me question his motives.”

“A political refugee, perhaps?” the Earl Curzon suggested.

“Quite possibly, sir,” Stern continued, “at the very least, he is a man with much to hide, but as of yet - I have no reason to question his capabilities, only his motives.”

“And that,” Lloyd George said, “is surely immaterial so long as it helps us to achieve victory in this conflagration.”

“I still find it totally unacceptable that we have taken this fellow’s designs at face value,” Crompton muttered, “especially one with no credentials.”

“We did it because he is good!” Swinton snapped, “look at them” he said, throwing the blueprints down on the table, “he practically sketched these out from memory on the back of some blotting paper - we cannot ignore talent like that, regardless of the providence!”

“Quite so,” Tennant said, “although it would not do much good to project his influence much further - the diplomatic consequences of doing so could be - a-ha - rather unpredictable.”

d’Eyncourt clapped his hands together.

“If I may bring this matter to a close, gentlemen,” he said, “I would like to now draw the Committee’s attention to the proposed timetable presented for your deliberations on page nine...”

-----

(Taken from ‘The Ikari Doctrine: Technological Developments as Wartime Propaganda’ by William Dalrymple in “The Journal of Military History” April 1981)

“Gendo Ikari’s initial involvement in the development of military hardware was kept entirely out of the public domain. His initial appearance on the front lines, well out of the way of the war reporters, was easy to hide - as was his transfer from military custody on the Western Front to the engineering works in Lincoln. The Defence of the Realm Act of 1914 (better known as DORA) had already given the government de jure as well as de facto control over the media - whilst all civilians involved in munitions production remained tightly monitored by military police.

It is certainly true to say that racism played a role in the unwillingness to acknowledge Gendo Ikari’s initial work, although perhaps not as much as would be assumed. In the Edwardian period, Japan - the first ‘Asian’ country to fully industrialise was fundamentally considered to be a western nation in outlook, if not ethnicity - and many prominent figures remained respectful of their colleagues in Tokyo, especially following the Japanese Navy’s role in subduing the Sepoy Mutiny in Singapore in February 1915.

However, the obvious propaganda difficulties in associating a foreigner (not to mention one lacking any formal documentation) with the pinnacle of wartime engineering was obvious. Upon his transfer to the United Kingdom on 26th December, Ikari was refused any communication with the outside world, aside from figures directly involved with the Landship Committee (later to become the Tank Committee, and later the Evangeliser and Bio-Mechanised Infantry Division) - whilst perfectly understandable of the time, surprisingly few objections seemed to be raised regarding how Ikari’s relative isolation from the public eye could be used to his own advantage...”

-----

(Stadtschloss, Berlin

26th December, 1915)

Kaiser Wilhelm had not enjoyed the Christmas period. Already outmanoeuvred at a personal level by the likes of Falkenhayn and Hindenburg, the Kaiser had spent most of the year watching his nominal position as Supreme Warlord be reduced to little more than a figurehead. On his most recent visit to Große Hauptquartier earlier that month, he had done little more than chop wood, hand out a few derisory medals and be lectured at by Ludendorff.

He gave an approving nod at the man sat opposite him in his salon. General Lorenz was one of the few senior members of the Supreme Command that actually seemed to treat him genuine respect, rather than a propaganda tool.

“Even if the lines hold,” Lorenz said, “which - admittedly - I believe that they will, it still ignores the fact that our supply lines are entirely reliant on the successful utilisation of the Home Front, which is simply not what is happening at the moment in time.”

On his few excursions throughout Berlin, the Kaiser had noticed the gradual changes amongst the population. The growing wanness and listlessness of the civilians, the darned clothes, the flowers slowly being replaced with vegetables. The effect was subtle, but it was increasingly apparent that things were not quite as rosy as Command insisted.

“You sound like you have something in mind, my deal Kiel,” the Kaiser said.

“Not quite yet, sire,” the General said, “but I have allies, friends almost, that remain close to the levers of power in other capitals - I do wonder if plans are emerging that could prove of benefit.”

A dark look came over the man’s eyes.

“Matters are coming to ahead at a rate that I am surprised by,” he said, “it seems odd that man can so easily be swayed from his predetermined path, even as God insists that he takes the one that had been created for him.”

The Kaiser chuckled.

“You sound like you have been speaking to praeses Winckler again!”

“It is a spiritual time for all of us, mein Kaiser”, the General replied, “I suppose I am still rather full of the Christian zeal.”

For a while, the two man said nothing, simply relishing a rare moment of silence. After a minute or so, Lorenz spoke again.

“If I may be so bold, sire,” the General said, “it may be time for us to consider reaffirming the Christian morality of our fighting men - whilst I quite understand the difficulties associated with getting the Catholics and the Calvinists to agree on anything much - I think we can all agree on the benefits of a sound moral and theological underpinning of our mission.”

The Emperor of Germany and King of Prussia leaned forwards.

“You sound as if you have something in mind.”

Lorenz paused for a moment, before walking across to the map of the world that covered one wall of the room. He pointed to a location somewhere in the Near East.

“You know,” he said, “it is nearly two-thousand years since the Messiah was born around there.”

The Kaiser raised an eyebrow.

“With respect, General, I am quite aware of that.”

“Of course, sire,” Lorenz replied, “I am just conscious of the cultural sensitivity of the region, especially given the threatened Anglo-Egyptian incursions into the Sinai and Palestine - Herr von Kressenstein is a superb commander, but...”

“Yes?”

“I fear for a number of matters if the Holy Land is threatened. Tell me, mein Kaiser, I wonder if you are familiar with the theological history of the Dead Sea?”

Last edited by

Lord Roem on Mon Aug 18, 2014 10:47 am, edited 1 time in total.

[/center]

[/center]

But he's gonna be WAY too old for Yui if she isn't even born yet, so still not seeing what the hell he hopes to accomplish here.

But he's gonna be WAY too old for Yui if she isn't even born yet, so still not seeing what the hell he hopes to accomplish here. [/img][/i][/center]

[/img][/i][/center]